I’m Sorry About this Thing I Made in the Darkness

Text by Silja Nielsen

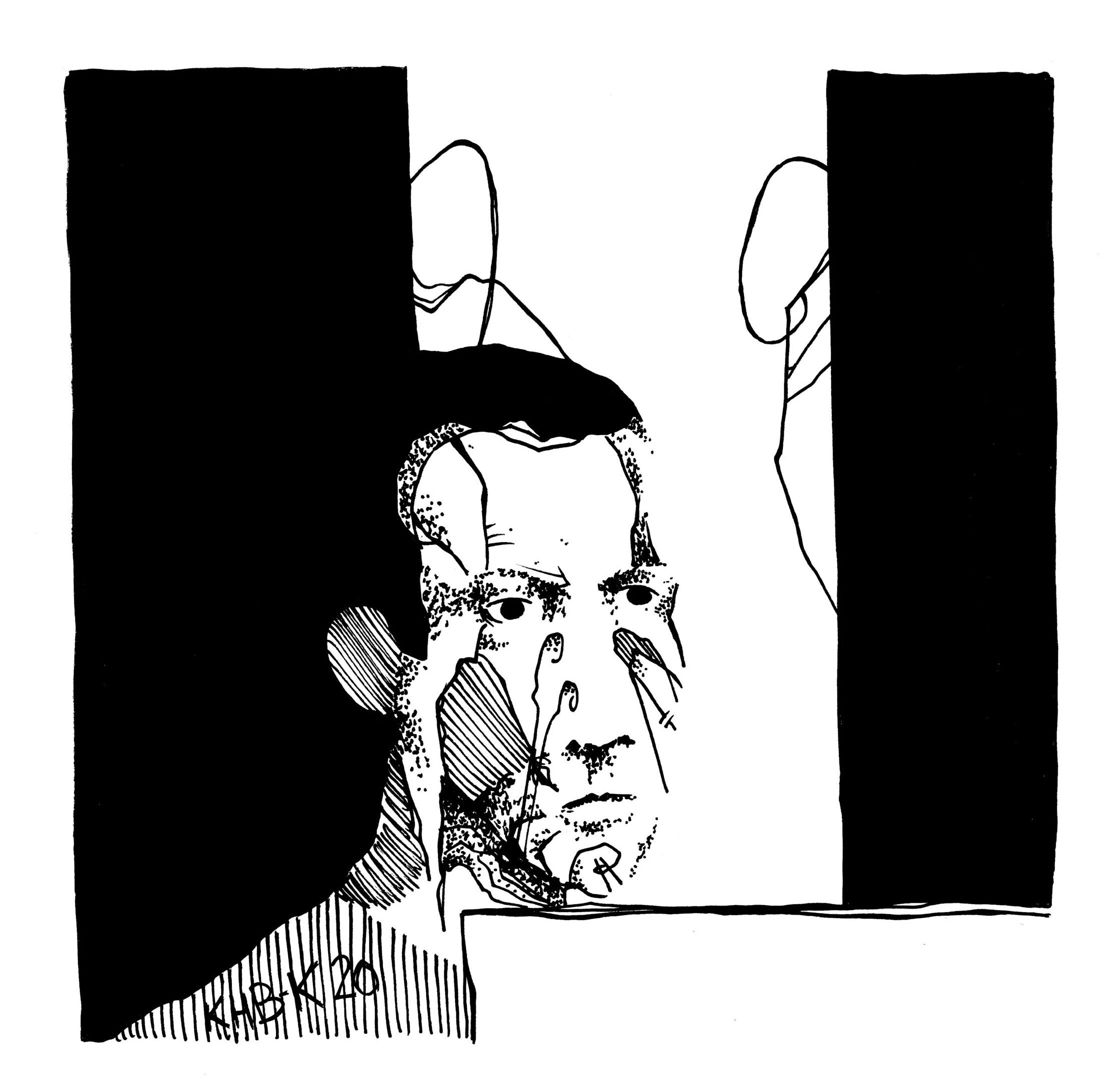

Photo by Simon Buchou

I listen for you both as you walk around the house, I look at you when you are in the part of the garden I can see from here. In and out and around since you showed up a little after dawn. You said your names were David and Ali, and that you were soldiers. You didn’t ask if you could search the house or the grounds. I don’t like it. I know you have noticed something. About me, about the surroundings, either, both.

You gave me these odd looks the last time you were in here. I sit and tend to the fire. We’ll want the fire tonight, you have to stay, you didn’t come by car as you said. You won’t be able to make it far enough on foot, and if you’ve been eyeing the car Ada and I came in, forget about it, there is no equipment to charge the battery from the solar generator. I would have heard your car, that’s how silent it is, and I listen all the time. If you had had a car, would you have taken me with you? I heard your steps in the gravel, but didn’t think it would be you, or, well, someone like you. I mean, you’re human. I don’t like that you’re here. You make me think of Ada. You make me feel like I still have someone to be responsible to. You haven’t been down by the lake yet, have you? I can’t see everything from here. Ali, I just saw you pass by the window. Perhaps one of you stood on the shore and looked out over the surface of the lake. Beware. It’s a steep drop covered up by rotten leaves and the water is freezing cold. Ada once jumped in. I was afraid she would never come up again. Perhaps the smell of rot warned you to take care and not walk too close. Perhaps you just knew.

Smell has become very important to me. One infection while I’m on my own and I’d be done for, I know that. Most of the food is still good if eaten immediately from the cans. I’ll give you some, if you ask. But maybe you have already found it and won’t ask. The smells that haunt me are those of rust cutting through meat, a searing pain from the trap, and the trap is very real but the pain is almost not. I’ve forgotten most of it but the sour smell of infection, not my own flesh, it can’t be, and anyway, it was a long time ago. I can almost banish the sight of my leg caught between the claws of the trap, bleeding my life away, from my mind. It was different with the smell of the infection that followed, it stayed with me, sour like vomit and muscles crumbling, interlaced with feverish dreams. I drowned the sight and the pain in the lake, and I hoped to eventually drown the smell with it.

When you asked me if I lost that part of my leg “in all of this”, I nodded and answered, “hunting trap”. I laughed and followed up with “it’s stupid, right?”, but neither of you as much as smiled. That was one of the first things you asked about. Ada and I found the trap in the utensils shack and put it up ourselves, that’s how stupid it is, I didn’t know exactly where she had placed it. I haven’t told you about Ada yet, but she’s the one who saved me. She meant well with doing what she did to keep me alive, and later, when I was done screaming, I could understand what it had taken out of her, how much she had suffered as well.

We lived together for ten years; did you know? No, you don’t know yet, but I’ll tell you. I’ll tell you we were happy. I’ll tell you that bit first, to win your good-will. Perhaps. You’re both men, and you’re soldiers. At least you said you were soldiers, and you wear uniforms, but you came by foot. David, your uniform is patched and hanging loose on your body, your stubbles are days old; Ali, you look even worse: Your eyes are haunted and suspicious, darting from my face to the windows, to the door, you’re unable to just look at me, and I’m unsure how much you are listening to what I say. None of you have come close to me, you stand just inside the door when you speak. I don’t want to have any prejudices, but I can’t help but think: Perhaps you won’t be sympathetic to my story after all. But I have to try.

I have so many memories of her. But only some of them are relevant to what I have to tell you, and I sort them in my mind: She came home and told me that there was no time for questions. That was three years ago, before “all this”. To trust her, that was what she asked, she would tell me everything later. To pack as much as I could in half an hour. Pretend we were going on a camping trip. A long camping trip. We stopped at a convenience store, took as much non-perishable food as we could, people stared, an elderly man behind us with a grey front tooth asked us if it was the apocalypse.

Turned out that it was. We hit more stores before we headed for a secluded house her parents owned when she was a child, and where they spent their summer vacations. It had nothing but fir trees for neighbours. That was the hiding place she chose. Her parents sold it years ago. We broke in. Then we watched the news on my laptop, barely left the screen for days, until the news broadcasts stopped coming, and shortly after we lost the internet connection. If you were in a place where you could hear the news, I believe you can understand why I thought everyone was gone. How are you not?

Ada and I settled in here for good. We chopped wood for winter and dug gardens we would plant in spring, but in early autumn there was the accident with the hunting trap, and I lost that part of my leg to the infection.

When I came around from the fever, we were deep into winter. Ada died while I was still spending most of my time recovering on that sofa, looking out of the window and waiting for her to return. She tried to repair the roof, and I’m fairly sure she broke her neck in the fall. She was dead when I got to her. I knew I had to bury her and would have found some way to do it the next day, even if I had to dig with my hands, but an animal, a wolf, carried her away. I saw it from the window, right over there, but I can see you don’t much believe me when I point. There are no wolves around here? How do you know? Well, I know what I saw even if I haven’t seen it since. I won’t insist it was a wolf, but it was a big animal with four legs that looked up at me behind the window as if to say: “You’re next!” before it dragged Ada’s body in between the trees.

I wish I had better crutches, I tried to cut some, but they never got better than those Ada carved and they’re not good. I mean, you can probably see it just from looking that they’re no good. I can’t get up on the roof to fix it. I sleep right in front of the fireplace all winter, autumn and spring, and you won’t believe the pains it brings me to chop the wood I need. But I survived that winter and the other two.

Who knows, if you hadn’t come around, I might even have survived this one. We had a lot of rations. They last even longer when they’re just for one, and I eat sparingly. The garden and the fruit trees help a bit. I can’t get myself to calculate properly, but I think maybe one more year.

I wish this was the only story I was telling you in between your coming and going. It’s the standard survival story about losing everything. You’ve heard it a thousand times, haven’t you? I have. We grew up with them, right, only this time it happened to all of us, if the cyber silence is to be trusted. It’s the story about turning your back to civilization to preserve your own lives, Ada leaving her post as a nurse to save us instead. She saw one of the doctors sneak away, and everyone was already uneasy with not being told what was wrong with the patients they were about to receive. They were friends, Ada and the doctor, so he told her. She said he was told by someone on the governmental disaster team who also ran. You’re not here for Ada, are you? No? Okay. I didn’t think so. I suppose it wasn’t so bad for me to run, but I still had family and friends. I only warned them once I was in this house and the news had already broken. We kept in contact for as long as we could, but my phone hasn’t had signal for three years. I keep charging it and sometimes I listen to the three songs I had downloaded.

You can borrow it if you want. I told you about Ada. Won’t you tell me why you came out here, why you are so restless, I think it might affect you differently. I want to know.

So, you won’t settle down here and talk to me? What are you doing out in the back? I can’t see you from the windows. I imagine you will sit down, come nightfall, when you hear the sound from the lake, like a gaping mouth trying to breathe, and the temperature drops ten degrees in a matter of seconds. I don’t understand the thing in the lake, what it is, and where it is trying to find its way to, but I helped it some of the way, and I shouldn’t have, and I don’t think I can stop it.

I’m sorry about this thing I made in the darkness. I’m not happy to see you. I thought I was the only one left, and I sort of … when I found the book, I didn’t think it would hurt anyone, because I thought there was no one left to hurt. I don’t really know how to say it. I take the book from my bed and flick through it. The author claims he never tried any of the rituals, that it was just old myths and things he made up for fun. The last one, the one I tried, is the worst one, the one about other-dimensional creatures you can call out to and they will use your mind as a sort of beacon. He wrote that he couldn’t gauge their strength or size as if he had seen them, only not clearly, but I got the impression they were big. Big, chimera-like creatures, fashioning themselves out of parts of consumed worlds, wanting to come here as well if we let them. But if they came, they would be company, right? There are no fancy rituals like pentagrams or bloodletting. Just read the pages, say the words and think. They’ll come through you. Your mind is the gateway. Think about letting the creatures through.

For a while it felt like I was thinking thoughts not my own. Like I was high on the drugs one of Ada’s friends once gave out at a party. Like I was talking to someone not in words. I don’t know if it makes any sense to you, but does it talk to you from the lake? I hope it doesn’t, but please just tell me. It didn’t settle with me, it went for the lake, and I was just as alone as before. I didn’t think it was actually there until I heard it breathe. And then I didn’t mind. After all, it could only hurt me and the forest creatures, and I didn’t mind too much. I think it actually helps me so far because sometimes there are tracks to the shore, and I think it takes the animals that would be dangerous to me. I like to think that it took the wolf.

This is the point where I need your sympathy. I thought everyone else was dead, that it was just me, and that I wouldn’t even survive the second winter because it was so cold. The stories and pictures in the book about chimeras stealing humans to their dimension, of ripping them to pieces, turning every place they come into contact with unlivable. What did it matter? Please also know that I didn’t think it would work. But if it did, who would it hurt? Why was that book in this house? Must have been those who owned it between Ada’s parents and our squatting. Ada didn’t know anything about those people, but they left all kinds of strange things. You’ve probably seen them upstairs. We put them all into that small room next to the chimney, had good laughs about several of them, but before that they were everywhere. This book was one among many odd books, only this one is handwritten. It doesn’t seem old, but I don’t know if there are really scribes these days who copy entire books by hand, including redrawing and colouring the pictures. It would take forever, and it is hard to imagine doing it in the time where you could get unlimited copies with a click. More likely he wrote it than copied it. Right?

Really, Ali, look at me. I know I’ve been talking for a long time, but it is important. So now I turn and follow your gaze out the window, but there is nothing right now.

Yes, of course you can see the book I talked about. It is right here. But don’t go to the lake, especially not now. It’s worse at night. I don’t know why, it just is. Don’t try to think about the creatures while you say the words, it really works, and I wouldn’t have done it if I had known you’d come.

Won’t you tell me something now? Who sent you, what is happening back in civilization? Is there anything left of anything? Ali, you tell me everything will be fine. David, you nod eagerly. But it’s not what I want to know, and I thought you would get to the things I want to know, you just look at each other and at me, and suggest that you can go sleep in the car you came in. I know you’re lying about that car, but not what to do, I offer you my place by the fire, I can sleep in a different room. But you’ve made up your minds. No, don’t go. You can sleep in the car Ada and I came in. I don’t know if it will protect you, but it’s worth the try. You won’t take the keys. I tell you I know there is no car, and then I tell you once more not to go near the lake, because that is where it went, after I imagined it, breaking the steel surface with big heads unlike our own, swimming to shore, strong arms dragging them up through the rotting mud bank before they make their way to the house, and since then the lake breathes at night, wet breaths in and out, can’t you hear it? I think there was only one to begin with, there are more now. David, you nod before you catch yourself and look at me and tell me no. No, there is nothing.

But your expression, the way you almost stand back to back with Ali who is watching the door says yes.

And then you leave in wordless agreement with each other. You leave with the book. My book. I hear the front door close. A whiff of very cold air hits me from the outside, and the fire in the fireplace flickers. I feel very sad, it is a heavy, dark feeling. I want to tell you that I’m sorry when I can hear the creatures move around out there. I stare at the fire and refuse to look outside. I’ll never know what you were here for now, will I? Perhaps you were just here to help me, to find survivors and then came in doubt because of my story; perhaps you were hiding, if there is still anything to hide from.

I don’t think you were really soldiers. It’s been a long time since I checked phones, and internet and I try tonight, but there is no connection. I don’t sleep. I want to listen to my music, but I especially don’t deserve it tonight. I listen to the breathing and think, maybe because I made it it will come for me last.

In the morning, I force myself out of the house on my bad crutches, I examine the tracks left by you. The book is there, blotched by moisture, but I still take it, carry it inside. I call your names.

The air is almost warm, but with a cold edge from the shadows. The warmth feels so good on my face. I should bury it deep in my memory for winter. I wish I hadn’t made that thing in the darkness, and I’m sorry about it, and I’m sorry about what happened to you because of it. I follow the tracks to the lake shore where something big has slid down and probably taken you with it. I walk all the way to the main road that day, but as I expected, there is no car nor traces of one. I stand there for hours, as I’ve done many times before, but no one comes by.

About the author / Om forfatteren

Silja Nielsen was born in 1990. She holds a Master’s degree in philosophy from the University of Copenhagen, and aspires to become a full-time writer. Silja has a brilliant imagination, creates insane scenarios and writes fascinating stories about technology, horror and the downside of science.

Silja Nielsen er født i 1990. Hun har en kandidat i filosofi fra Københavns Universitet, og arbejder på at blive fuldtidsforfatter. Silja har den vildeste fantasi, udtænker syrede scenarier og skriver fascinerende historier om teknologi, horror og bagsiden af videnskaben.

Du vil muligvis også synes om

Mit farvefjernsyn er gået i stykker, og Gud er ligeglad

7. oktober 2020

Samfundsfjender

18. november 2020